Vor dreissig Jahren wurde die Musik-Szene Manchesters für immer verändert. Paul Morley besuchte die Stadt seiner Jugend und beschreibt die damalige Zeit im Observer vom 21. Mai 2006. A northern soul

A northern soulThirty years ago, the Manchester music scene was changed for ever. Paul Morley revisits the city of his youth and recalls the sights and eviscerating sounds that transformed the lives of a generation

Paul Morley

Sunday May 21 2006

The ObserverIn 1976, if you were a teenager in and around Manchester, which was a city still covered in war dust and with streets seemingly weakly lit by gas and an economy financed by pounds, shilling and pence, and you a) read the NME; b) wanted to write for the NME, or just send them letters every week, signed Steven or Morrissey; c) were intimate with the Stooges, the Velvets, Patti Smith and Richard Hell; d) were poor but had a few pence in your pocket; or e) were bored with Dark Side of The Moon, which didn't seem as much fun as the dark side of the moon, then you'd go and watch the Sex Pistols twice at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June and 20 July.

Those two shows started the process that led to the actions that inspired the creative energy and community pride that pieced the city back together again and which led to it being filled - splendidly and somehow sadly - with light and lofts and steel and glass and sophistication.

Over a hundred years after the Industrial Revolution, which seemed destined to crush the area into dust and isolation as the world it inspired moved Manchester out of the way, an Emotional Revolution happened that would push Manchester into the 21st Century. This happened because Johnny Rotten showed Howard Devoto a way to exploit positively his interest in music, theatre, poetry and philosophy. Devoto, let's just say, for the hell of it because the story has to start somewhere, with a bang, or a legendary punk gig, was the man who changed Manchester because he had an idea about what needed to happen at just the right time in just the right place. He arranged for the Sex Pistols to play in Manchester before the rest of the country had caught up with the idea that there was any such thing as a Sex Pistol. In the audience for the shows were Mark E Smith, Ian Curtis, Morrissey and Devoto himself, four of the greatest rock singers of all time, directly challenged to take things o

n. Johnny Rotten was like a psychotic lecturer explaining to these avant-garde music fans exactly what to do with their love for music, the things they wanted to say, and their unknown need to perform.

Buzzcocks formed in time for the sold-out second Pistols show, and became where Beckett met Bowie, or so it seemed to me as I followed them from gig to gig in the new clubs mysteriously opening up underground in cramped drinking dives or overground in grubby pubs and decaying bingo halls. With Pete Shelley on cheap guitar and the viciously smart Howard Devoto singing songs that had already abstracted the idea of the Pistols' punk into something seething with thought, history and humour, Buzzcocks made a sour sort of brainy bubblegum pop. Our very own Buzzcocks joined the travelling carnival with the Pistols and the Clash and showed everyone in Manchester who a) read the NME and b) wanted to form a band, the route from nowhere to more or less somewhere.

1976 ended with the Sex Pistols' Anarchy tour playing Manchester twice when most places in the country wouldn't allow the group inside their boundaries even once. They played the Electric Circus, a heavy metal venue a couple of miles up Rochdale Road in Collyhurst, abruptly co-opted by a new scene that needed venues to cope with this new audience. The Pistols sort of felt like a Manchester band, and there was Buzzcocks, local lads, playing - plotting - with them as they invaded and outraged this dull, drab land.

Coach trips would be organised, leaving from Piccadilly Gardens in the centre of town, 75p a ticket, heading for places around the country where the Pistols would be playing under various aliases, to avoid the censoring wrath of local councils. Malcolm McLaren, the Pistols' manager, would put the whole coach load on the guest list. The young people of Manchester, including various Buzzcocks, would arrive to see the Spots - the Sex Pistols On Tour Secretly - in Wolverhampton, and walk straight into the venue and into the very heart of the deliciously forbidden action.

Just after Christmas 1976, using a loan from guitarist Pete Shelley's dad, Buzzcocks recorded their Spiral Scratch EP with producer Martin Hannett, a local lad from the dark side of Mars. He was the city's Spector, the region's Eno, the man who produced the sound of Manchester, forcing the spacey, twisted highs and thumping lows of his life into the local, cosmic and carousing music that would soon follow Buzzcocks. Spiral Scratch was released on the bands own New Hormones label at the end of January 1977: four brief songs, four monumental miniatures, four stabs in the light. It was meant merely as a memento of the adventure they'd been having, a way of recording this lively little local disturbance. They hoped to sell at least half of the 1,000 copies so they could pay Pete's dad back.

The Spiral Scratch sleeve was black and white, the music was black and white, the landscape their songs occupied was black and white and it was the last time Hannett's production would be so black and white. The vivacious intelligence and dry, saucy wit was smuggled in behind the austerity. It was as though the group was clinically scr*pping bloated rock history, and finding a very particular position where things could start up again. Perhaps, if you like, Spiral Scratch was the first real punk record, the birth of alternative indie culture, the rich, compressed source, ideologically if not sonically, of punk, post-punk, new wave, grunge and so on.

Certainly, at the time, as the person who had shoved Morrissey out of the way to become the local NME reporter and whose first review was of the sixth or seventh gig played by Buzzcocks (Billy Idol's Chelsea were supporting and Devoto looked like an emaciated glam rocker from a sci-fi Poland), I was making out that this record had a kind of power that would last for ever. I also sort of believed that none of this would ever go anywhere beyond the city limits, would never mean anything in, say, the next year, or in 1980, even as I started to follow Buzzcocks to Liverpool, Leeds, London.

We never thought we were ever going to be nostalgic about what was happening. We would die first, or retreat into a Rimbaudian silence. The me-I-appear-to-have-been-back-then, bursting into 1977 as an NME writer covering the music scene in a city where it was opening up just as I needed something to write about, would tell the-me-I-appear-to-have-become to OOOPS off for being nostalgic. This now-me would not tell that then-me to OOOPS off in return because I am aware of what was about to happen, which made Manchester the best place in the world to be and the very worst place all at the same time. It became a place to escape into, and a place to escape from.

During 1977, lost to myself as I was following the creation of this endlessly exciting new scene, my father killed himself. The year split into two. One 1977 where everything collapsed and closed down. One 1977 where the world was opening up.

If you a) read the NME and b) had started a fanzine that was a Manchester reply to Mark Perry's Sniffin' Glue - I had, and Perry wrote me a note, saying that my effort, Out There, printed on glossy paper, looked posh like Vogue - one week you'd be seeing the fem-crazed Slits in a pub called the Oaks, a two-mile walk from my house in Heaton Moor. The next week back at the Oaks you'd be hearing a freshly formed Siouxsie and the Banshees still working out their sound. You'd be writing poems about Gaye Advert for fanzines called Girl Trouble.

As John Cooper Clarke matter of factly said about what happened after Spiral Scratch - one thing would start another. 1977 was the year that everything sped forward faster and faster as things led to other things, as local action spurred more local action, and by the middle of the year it seemed as if there was a gig to go to every night at a new venue, a new band to see every week with a new take on things, and hordes of eccentrics, enthusiasts, loners and hustlers suddenly having places to go and ambition to fulfil. Suddenly, there was a community.

We sort of took it for granted that the scene would include a demented poet who made you laugh before some group or another got angry about something or other. Cooper Clarke was a skinny vision in specs and bone-hugging black who looked as if he'd fallen from the front of Blonde on Blonde into the streets of Salford and he fitted just fine on bills with Buzzcocks and the bands that were about to take part in the one thing leading to another, bands who hadn't yet sorted out their names.

By mid-1977, the instantly intimidating and incendiary Fall were blasting tinny sound into cryptic song, fronted by that creepily normal looking maniac first spotted violently heckling Paul Weller - 'f*cking Tory scum' - when the Jam played the Electric Circus. The Fall's first show seemed to be played in front of an audience that consisted entirely of the Buzzcocks. Mark E Smith's earliest performances, where he was often playing in tiny clubs or rooms that sometimes seemed to be where you were actually living were possibly the angriest thing you would ever see in your life. It seemed he was being so angry on your behalf. You sometimes didn't think he'd make it to the next song, let alone 30 years and 30 albums, some of which sound like they were made before they even existed. Through a harsh northern filter, the Fall channelled into their songs a night's John Peel show from the mid-Seventies, one of the darker, stranger ones on which he played rockabilly, dub, psychedelic p

op, garage punk, New York punk, English punk, Canned Heat, the Groundhogs, Peter Hammill, Henry Cow and Faust. The Fall might in the end be Manchester's greatest group, if only because there have been at least 20 Falls, one leading to another, all of them with the same lead singer, who's always the same and never the same twice.

In 1977, I somehow managed a band, the Drones, while simultaneously giving them bad reviews in the NME, because I couldn't bring myself to tell them to their face that they were a little bit too corny for me. I played and sang alongside photographer Kevin Cummins and Buzzcocks manager Richard Boon in the Negatives, the po-faced joke group who deleted their debut EP, Bringing Fiction Back To Music, the day before it came out, mainly because we never bothered to record it. We played a lot with the Worst, who made the Clash seem like Rush. Alas, their 60-second rants about police brutality and the National Front were never recorded. In my mind, and it might well have happened, a key Manchester night in 1977 was an anti-Jubilee show that featured the Fall, the Worst, the Drones, the Negatives, John Cooper Clarke, Warsaw and John the Postman. Buzzcocks would be in the audience.

Warsaw never made it, possibly because they weren't that good. They played on the closing night of the Electric Circus, the venue the locals had taken over and which had lasted only 10 frantic months before being shut down. We had plans to save it by occupying the premises after a two-night farewell show on 2 October, but that never came to anything. There was no time to be sentimental. Something else was always happening, because one thing was always starting another.

By then, bands were playing at the Ranch, the Squat, Rafters and the Band on the Wall. If you go in search of these places now, none of them has been turned into supersmooth loft apartments like the Hacienda has. They've just disappeared, as if they were never really there, or they're broken-down buildings not yet touched by the modernisation spreading through the city, or they're rusted doors that seem sealed and give no clue of the chaos and noise there once was on the other side. Warsaw became Joy Division, who would, in one way or another, make it. They played their first gig in January 1978. It was the month when Rotten quit the Pistols and formed, as if he'd had them in his pocket all along, Public Image Ltd. The events started in 1977 couldn't stop just because 1978 was in the way. Devoto had left Buzzcocks after a dozen or so gigs and the EP, deciding that what had become known as punk was all over now it was known as punk. He'd met Iggy Pop and handed him a copy of S

piral Scratch with the immortal words 'I've got all your records. Now you've got all mine.'

His new group Magazine accelerated into the hard and cerebral post-punk zone with their furiously articulate debut single 'Shot By Both Sides', released in January 1978 along with 'What Do I Get?' by Pete Shelley's Buzzcocks as they dreamt up punk pop. Joy Division's music was changed beyond belief from that of Warsaw's by the involvement of Hannett, whose influence helped bend their music into, and out of shape. The difference between Warsaw and Joy Division was the difference between the Sex Pistols and PiL, between sleepwalking and exploring outer space. By 1978 Manchester had Magazine, Buzzcocks, the Fall and Joy Division - music, rhythm and thinking that you now hear streaked across more and more new bands

Watching from the inside but on the outside of everything, the doomed Steven Morrissey still dragged himself around town, and tried to get involved. He was slowly planning his revenge on all of those who doubted he'd be anything other than the strange boy waiting for something that would never happen and who wrote to the music papers.

In May '78, The Factory Club had opened in decaying Hulme, which led to Factory Records, which led to the intensification of the one thing starting another, which has led to Manchester today, with a brand new history as one of the world's greatest music cities, with a brand new future as the hip, renovated place to live. The Factory designer Peter Saville, who generated images, accessories and styles that made and remade Factory's shifty, shifting mystique, is the city's creative director. The young man whose vague project was to invent a record label like no other by raiding the design history of the 20th century is now in charge of inventing the idea of Manchester being a city like no other. A city that has become what it has become for better and worse because the Sex Pistols visited in June 1976 and something started to happen.

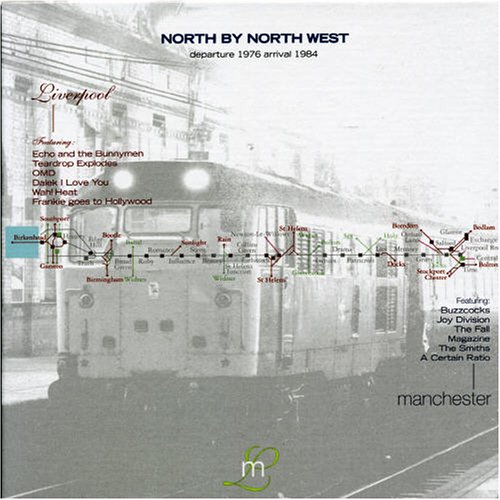

I have been putting together a compilation of music from the cities of Manchester and Liverpool between 1976 and 1984, called North By North West. It follows the music that was being made in the two cities because a group of people - an adventurous underground collective looking to establish their own identity - were suddenly shown by the Pistols, and the Clash, that they weren't the only ones having these thoughts, listening to that music, fancying themselves as the boisterous bastard children of Warhol, or Nico, or the New York Dolls, or Eno, or Fassbinder, or Marcel Duchamp.

Manchester and Liverpool were only 30-odd miles apart, and Eric's was one of the best music clubs of the period, so a few of us in Manchester would often make the journey in less than an hour, but the way the two cities' music developed during the few years after punk was vastly different. You can tell by the names of the groups. Liverpool names were eccentric, told stories and showed off: Echo and the Bunnymen, Teardrop Explodes, Big In Japan, Wah! Heat, Lori and the Chameleons, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, Dalek I Love You, Frankie Goes To Hollywood. The Manchester names were more discreet and oblique: Magazine, the Fall, Joy Division, Ludus, Durutti Column, the Passage, New Order and, ultimately, the Smiths. The music, while it shared the same influences, and was inspired by the same English punk personalities, sheared off in different directions. Only the Bunnymen and Joy Division retained any kind of remote atmospheric contact, feeding right into U2 .

The Liverpool scene started a little later. Historically it was tough to know how to avoid the trap of appearing to be creating another Merseybeat scene. Throughout the early Seventies, only Deaf School, a self-conscious sort of panto Roxy Music, gave any clues as to how to form a new Liverpool band without being the Beatles.

Eric's opened in October 1976 as a members club, which allowed it to stay open until 2am, and it started to put on the Ramones, the Damned, Talking Heads and Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers. The Spitfire Boys were playing Ramones covers on a Warrington bill with the Buzzcocks and the Heartbreakers by May '77 and as the only Liverpool punk group at the time, they would support all the visiting groups. They were the first Liverpool punk band to have a record out, but in a way their take on punk was a false start, and was soon overtaken by the Liverpool scenesters, jokesters, gossipers and posers who all acted like superstars when their only audience was each other. There had been an underground since 1975, with glam followers looking to create a New York type scene around their love for Bowie and Roxy, but for a while it was more clothes, and hair, than music. The vitriolic Pete Burns was the city's ultimate face with make-up better than any music he ever made.

Perhaps Liverpool was in some ways slow to get going because they didn't have the Sex Pistols visit twice. The closest the Pistols got was Chester some time in the autumn of '76. The big change in Liverpool happened when the Clash played Eric's on 5 May 1977, and Joe Strummer spent hours talking with half of Liverpool, or at least the half of Liverpool that was a) reading the NME; b) wanting to form a group; c) living more or less with each other; d) working out what particular pose would save their lives; or e) hating/bitching about members of other Liverpool cliques and clans and cults who just weren't cool enough, pretty enough, arty enough or good enough.

Three local pals were there for the Clash show. They were always there. There were at least a hundred regulars who turned up every week. The awkward, short-sighted Ian McCulloch, the gloriously garrulous Pete Wylie and the freakishly self-assured Julian Cope. They became a group that talked a lot about being a group. Wylie called them Arthur Hostile and The Crucial Three. McCulloch hated the Arthur Hostile name, and so they became simply the Crucial Three, a group who just talked about being a group, and how legendary they would be. Eventually, each member of the Crucial Three would form their own band and Wylie's Wah! Heat, Cope's Teardrop Explodes and McCullochs Echo and the Bunnymen would all play their first gig at Eric's - Teardrop and Echo on the same night in late 1978, a few days after the first performance by Orchestral Manouevres in the Dark. These last were electro-pop pioneers who slipped between scenes and crossed over into Manchester, releasing their debut singl

e 'Electricity' on Factory Records with the full Factory treatment - a glorious Martin Hannett production, a gorgeous Peter Saville sleeve and occasional contact with Factory's inspired and infuriating spokesman Tony Wilson.

If the Liverpool scene was a kind of surreal sitcom, then living next door to the Crucial Three, underneath OMD with their synths, and across the road from Pete Burns and his wife Lin with her kettle handbag, were Big in Japan. The Crucial Three loathed the camp, play-acting performance tarts Big in Japan, who were a kind of reverse super-group, a training ground for extrovert Liverpool characters destined for fame and notoriety. They contained Holly Johnson (later of Frankie Goes To Hollywood), Bill Drummond (producer, impresario, founder of Zoo Records and the KLF) Ian Broudie (Care, the Lightning Seeds), Budgie (Slits, Siouxsie and the Banshees) and scene queen Jayne Casey (Pink Military, avant garde impresario, and later spokeswoman for the Cream nightclub). Jayne shaved her head, screamed, wore lampshades for hats, Drummond wore kilts, Holly would also be bald with two plaits strung over his face. One song, 'Reading The Charts', was Jayne reading that week's top 40 over

a load of feedback. Big in Japan became so hated that a petition was organised which raised 2,000 names demanding the group be stopped. They were. Nothing could stop Echo, Teardrop and the various Wah! incarnations from taking over the pop world, except their own vanity and vulnerability.

As well as the compilation, I've been working on an essay for a book of photographs by Kevin Cummins that follows the Manchester music scene from the time the Sex Pistols played their two shows in June and July 1976 - stop me if you've heard this before - all the way past New Order via Happy Mondays and the Stones Roses through to Oasis, the Doves and beyond. There is also a book that I'm writing about the North itself - exploring the psycho-geographic idea of the North as a real place, and a dream place, and the differences and similarities between Liverpool and Manchester, Lancashire and Yorkshire. The book examines what it is that makes you northern, and what it means to be northern, and northern for life even if you move away. The sleeve notes for the compilation, the essay for Kevin's book, the book about the North that searches for the moments that sealed the northern-ness inside me, and this very piece I'm writing could all begin with the same words, because in the end

it's not about passively looking back, but acknowledging that history happens, and that's what makes the future:

"Eight days after the Sex Pistols played their first public date supporting Eddie and the Hot Rods at the London Marquee on 12 February 1976, two college friends from the north, Howard Trafford and Pete McNeish, borrowed a car and drove down to High Wycombe. The Sex Pistols were playing a show at the College of Further Education, supporting Screaming Lord Sutch. Howard and Pete wanted to see and hear for themselves this new thing that promised 'chaos' and not 'music'. This implied that whatever music there was, it was worth driving hundreds of miles to experience. After all, these two friends from the Bolton Institute of Technology had been drawn together through their love for Captain Beefheart, Can and Iggy Pop, and the understanding that if you formed a band you should know your way around the Velvets' 'Sister Ray' inside and out.

"They liked what they discovered in High Wycombe so much that not only did it focus their ideas for the band they were putting together but they were inspired to change their own names. In the new world the Sex Pistols were roughly creating, a change of identity seemed necessary. Trafford would become Devoto - Latin for 'bewitching' - and McNeish would become, romantically, Shelley - the name he would have had if he'd been born a girl. They would become Buzzcocks. They had the unusual desire to actually bring the Sex Pistols up to Manchester, and closely studied a tape they'd made of the gig so that they could work out what the Pistols were doing.

"If you lived in a city like Manchester, in the mid Seventies, you didn't really think of forming a band, unless that band sounded like it was from London, or even Los Angeles, or the middle of nowhere. There was nothing around to show you how to do it. Bands came to Manchester but they didn't really come from Manchester. It was the same with Liverpool. Then, inside a couple of years, all that was to change."

Sounds of two cities

Five classics from Manchester

1 'Boredom' by Buzzcocks from the Spiral Scratch EP (New Hormones)

2 'Transmission' by Joy Divsion (Factory)

3 'Shot By Both Sides' by Magazine (VIrgin)

4 'Bingo Masters Breakout' by the Fall (Rough Trade)

5 'This Charming Man' by the Smiths (Rough Trade)

And five from Liverpool

1 'Read It In Books' by Echo and the Bunnymen (Korova)

2 'Reward' by Teardrop Explodes (Mercury/ Island)

3 'Big In Japan' by Big In Japan (Zoo)

4 'Better Scream' by Wah! Heat (Inevitable)

5 'Relax' by Frankie Goes To Hollywood (ZTT)

Am 19.6. 2006 erscheint bei Korova seine Zusammenstellung

North By North West: Liverpool & Manchester from Punk to Post-Punk & Beyond 1976-1983 in einer limitierten Edition mit 3 CDs.